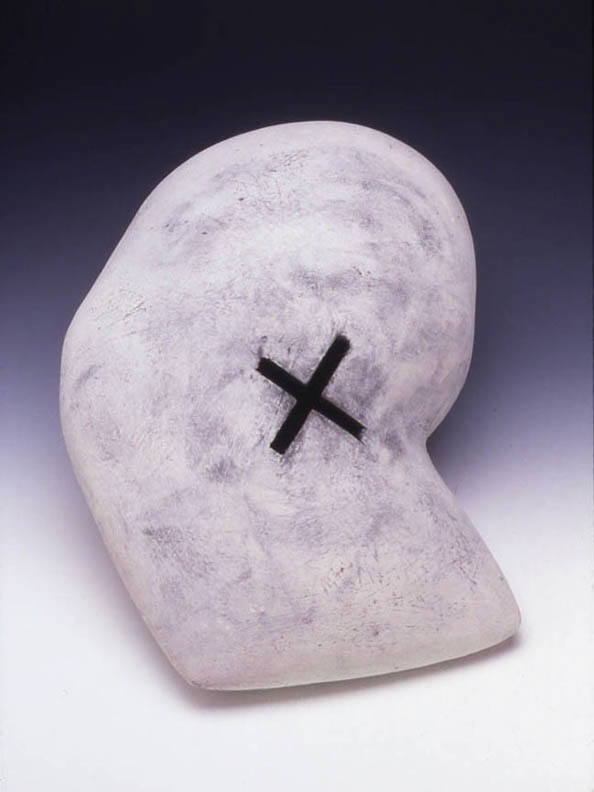

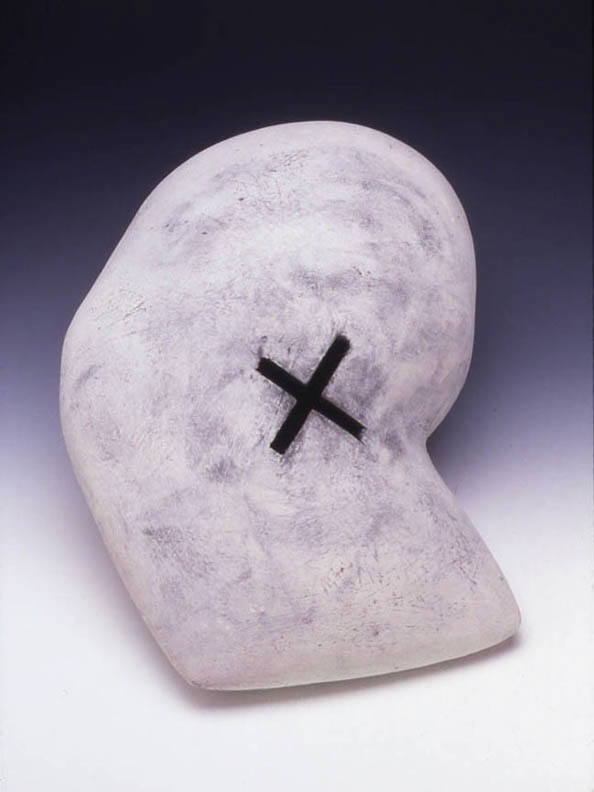

Gordon Baldwin

Gordon Baldwin

Gordon Baldwin

Gordon Baldwin

Gordon Baldwin

Gordon Baldwin

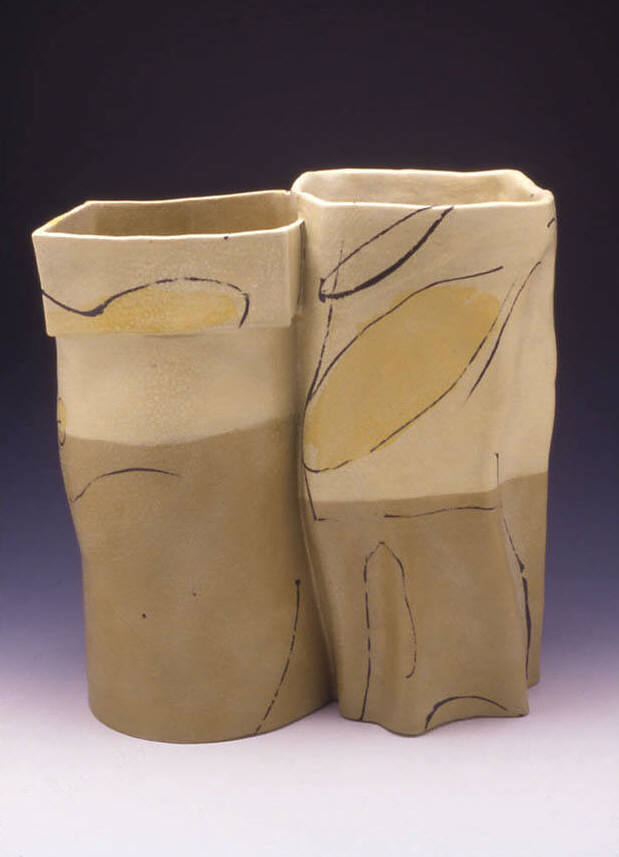

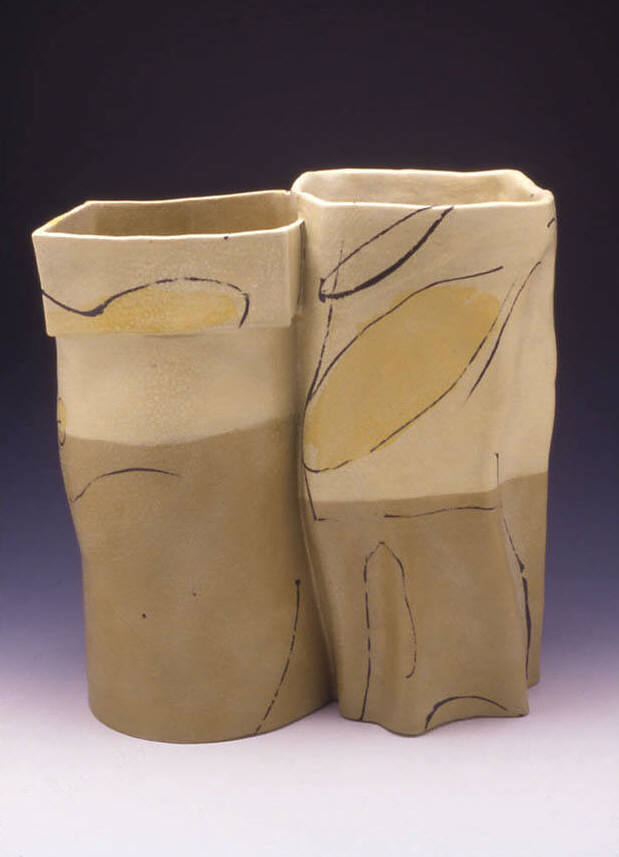

Alison Britton

Alison Britton

Alison Britton

Alison Britton

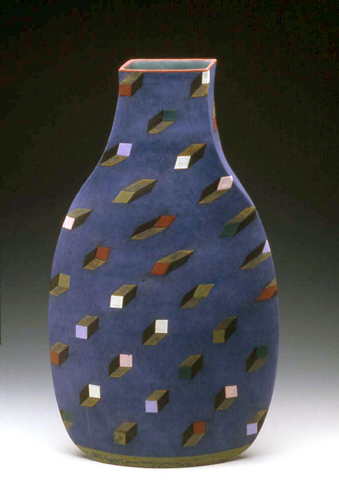

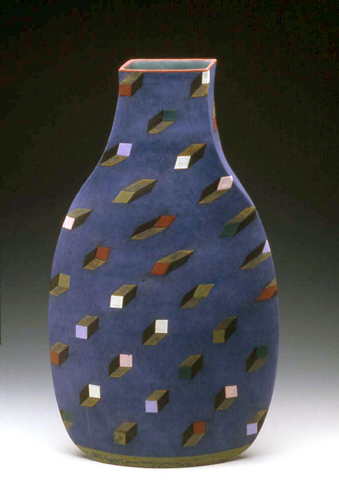

Elizabeth Fritsch

Elizabeth Fritsch

Elizabeth Fritsch

Elizabeth Fritsch

Elizabeth Fritsch

Elizabeth Fritsch

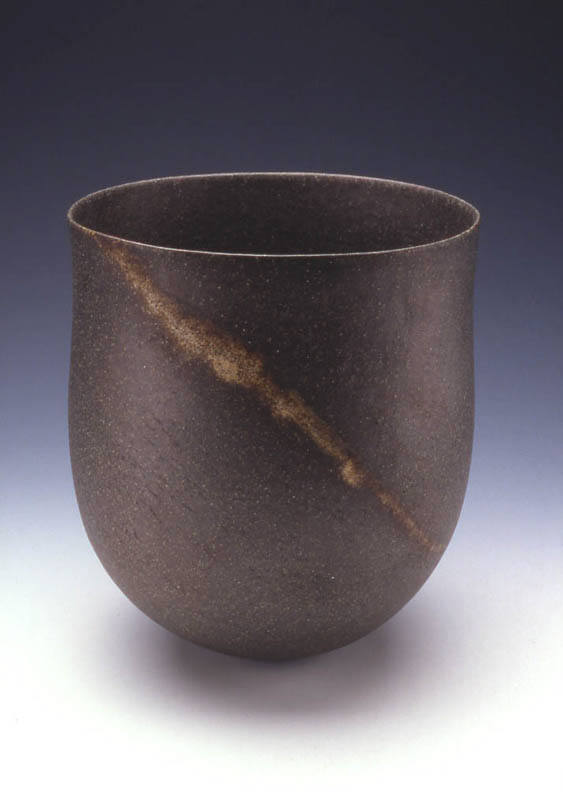

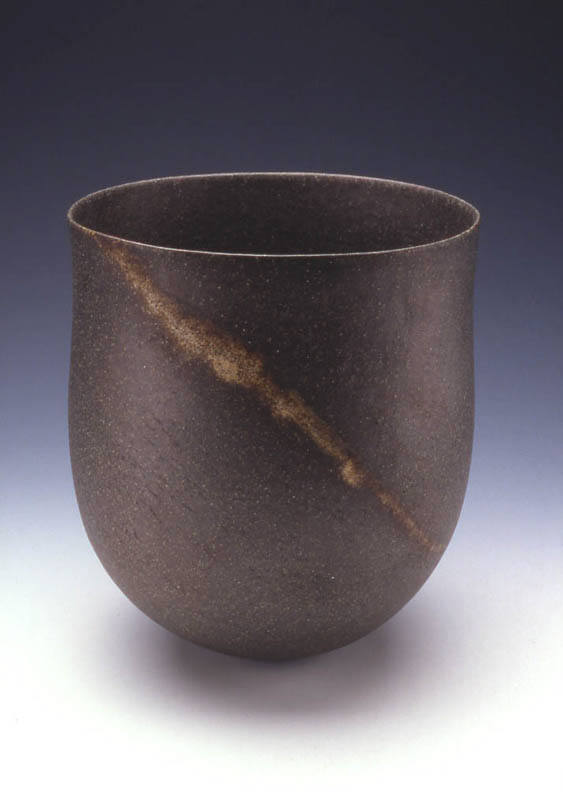

Jennifer Lee

Jennifer Lee

Jennifer Lee

Jennifer Lee

Installation View

Publication Photos

Publication Photos

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Pottery is at once the simplest and the most difficult of all the arts. It is the simplest because it is the most elemental; it is the most difficult because it is the most abstract. Historically it is almost the first of the arts. (Herbert Read, "The Meaning of Art")

"Pottery" is not the first term that comes to mind when considering the five artists in this exhibition, which, like much art in clay defies any simple definition; the work does not fall into any neat, prescribed category nor does it conform to any preconceived notion of "pottery". Nevertheless, while the highly individual ceramic pieces by all five is sculptural in intent, conveying far more than is presented, each artist has roots in the "pottery tradition" that feeds and nourishes the work. Herbert Read¹s observation, made in the early part of the twentieth century, used pottery as a generic term to refer to a wide range of ceramic objects, and his analysis is as useful today as it was in the early days of studio ceramics.

In this reference to pottery, Read goes on to say that the art of a country, the fineness of its sensibility, can be judged by its pottery, for it is, he remarks, "a sure touchstone". While this group of five artists is in no way fully representative of the diversity of ceramic art in England, and nor was it intended to be so -- it does not for example include any of the highly creative wheel-based work produced here -- yet the five artists are among the finest and most highly respected practitioners, investigating form, idea and process with integrity and skill. Interestingly, all share a common concern with hand-building in one form another, a technique that, unlike throwing on the potter's wheel, allows the slow evolution of form, enabling, even encouraging, contemplation and thought.

Hand-building, in a variety of manifestations, preceded throwing by several thousand years, and the revival of interest in the processes in the 1950s and 60s was in many ways part of a post-modern investigation into the clayness of clay, in which the hand rather than the wheel directs shape and form. With its apparent, but deceptive, lack of sophistication, hand-building allows the artist to shape and manipulate by such processes as coiling, moulding, pinching and slabbing, or a combination of any of them, although there may be little evidence of this in the final pieces.

Emmanuel Cooper

Frank Lloyd Gallery

131 N. San Gabriel Blvd, 103

Pasadena, California 91107 USA

PH: 626 535-9377